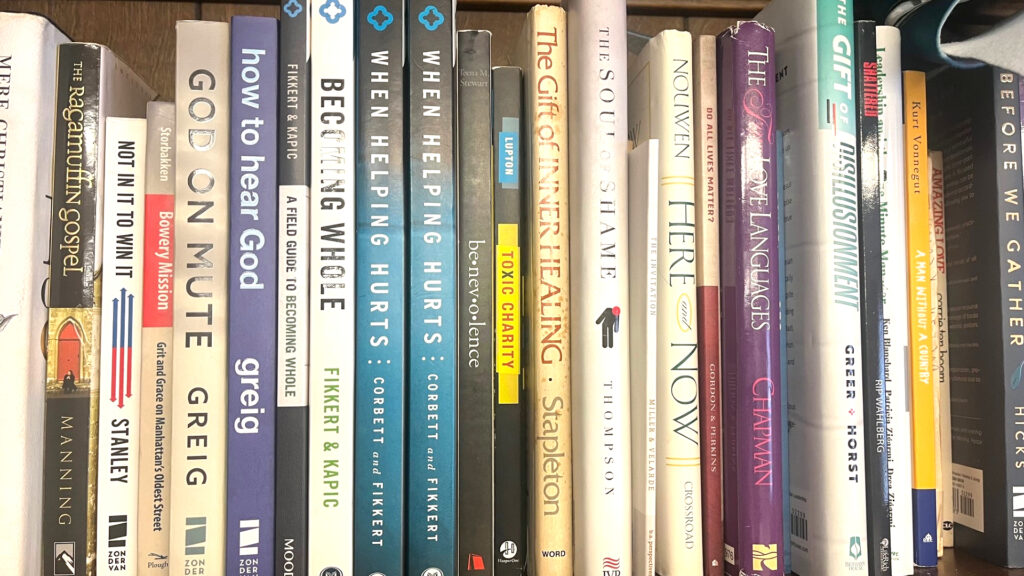

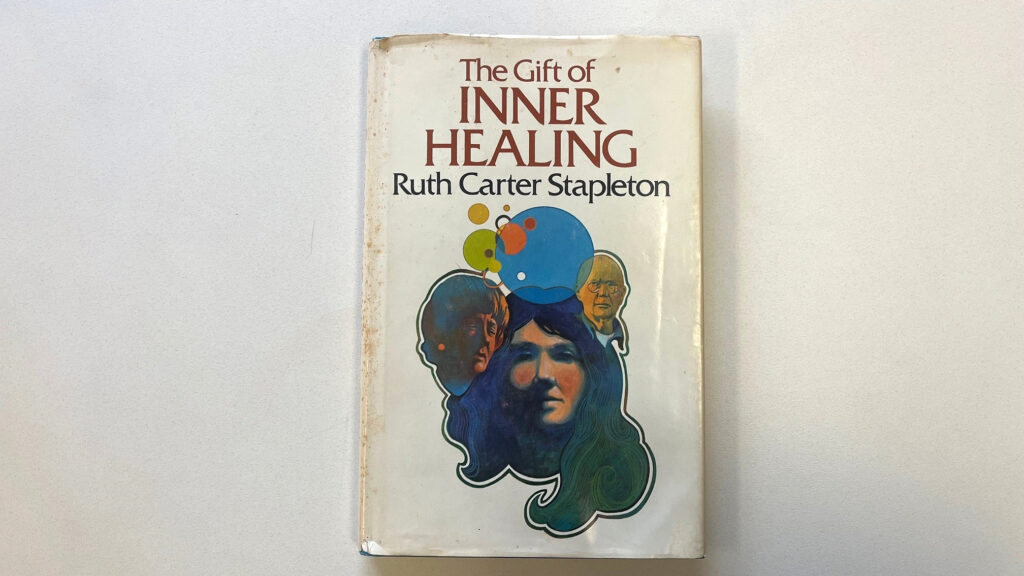

Ruth Carter Stapleton, known as the “Evangelist Sister” of President Jimmy Carter, also made a name for herself through her ministry, books, and teachings on inner healing from a Christian perspective. In the 1970s, Stapleton also founded “Holovita,” a Christian retreat and spiritual wellness center to help people invite Jesus into their past hurts and pains for greater restoration, liberation, and healing. As an established and talented writer, she authored The Gift of Inner Healing (1976), through Word, introducing a broader audience to her understanding of inner healing. Her convictions about inner healing emerged from a difficult season in her own life, when the care of a trusted friend who listened, reflected with her, and prayed for the healing of troubling memories helped her recognize and address wounds and pain that had not yet been healed from her childhood. Through that catalytic encounter of processing rejection in her life, her journey gave rise to an ongoing healing and reflective process rather than a single miraculous healing moment (Stapleton 1976, 14).

About The Gift of Inner Healing

In The Gift of Inner Healing, Stapleton shares that she now believes inner healing is an “experience in which the Holy Spirit restores health to the deepest area of our lives by dealing with the root cause of our hurts and pain” (Stapleton 1976, 9). The deepest unhealed areas of our lives, according to Stapleton, are the hurts, fears, and traumatic experiences which often manifest and present as anxiety at some moments but also “as backaches, headaches, skin rashes, asthma, and other illnesses” (Stapleton 1976, 9).

About Ruth Carter Stapleton

Though Stapleton held a master’s degree in psychology from the University of North Carolina, her conviction was that “some areas within our lives can only be healed by the power of the Holy Spirit” (Stapleton 1976, 10). I indeed share this conviction, and I believe that few in social services or the world of psychology, among those with a Christian worldview or faith, would disagree with her theological conviction. Throughout her book and her ministry, her unwavering Christian paradigm and faith permeate all she believes and the reasons she seeks to facilitate inner healing for the hurts, fears, and traumatic experiences others may carry. Stapleton continues to point out that there are events and people, such as psychiatrists, who can help us explore the unhealed areas in our lives, stating “Psychiatrists bring a degree of healing by probing into the past and bringing understanding of our weak and vulnerable spots and our angry and fearful reactions,” but “only the Holy Spirit can move back into these areas and remove the scars” (Stapleton 1976, 10).

I believe Stapleton’s conviction offers a prophetic challenge to a world increasingly focused on self-wholeness, inner healing, and other holistic practices that may resemble the restorative work of the Holy Spirit or Christian values, yet differ fundamentally in their core intent. For the Christian, the salvific deliverance of Jesus, the healing work of the Holy Spirit’s presence, and a relationship with God the Father are central. In contrast, in psychology, the social sciences, and holistic wellness, the focus is placed on the pursuit of the “best self.” In the former, the best self emerges through a restored relationship with the Creator; in the latter, the best self is a facade in which identity is created by the pursuit of affirmation, ambitions, and appetites in the moment. If we are to pursue the restorative healing of others, we must remember the actual agent of healing, the Holy Spirit, whose work takes place as we invite Jesus into our lives and into the dark places we are often afraid to enter.

An Honest Take On The Gift of Inner Healing

This short read, just over 110 pages, may be better suited to today’s context as a blog series rather than a book aimed at a broad audience. It is difficult to imagine a publisher today producing a mass-market paperback or hardcover that consists primarily of narrative stories rather than a sustained argument with theological depth. For readers wondering whether the book is worth their investment, it is best approached as a collection of stories accompanied by Stapleton’s reflections, rather than as factual, academic, or research-driven work. As I read, I also noticed Stapleton’s unique narrative style. I wondered whether creative liberties were taken in some of the dialogue, as it seems unlikely that such detailed exchanges could be recalled verbatim. At times, the stories felt more parabolic, similar to the narrative style used by Patrick Lencioni, serving to set up key points rather than provide detailed or strictly historical accounts. However, her points are apparent. As followers of Jesus, we often pray for the healing of physical symptoms as we are commanded to in the scriptures. Still, sometimes we do not see much healing, perhaps because we are expecting God to “heal the symptom rather than to make us whole”, thereby stating that we are praying for the wrong problem altogether (Stapleton 1976, 9).

Healing then comes not always through the laying of hands, but sometimes through the inviting of the presence of Jesus into the years of our lives, praying in a way while “imagining Jesus moving back into our lives, we picture the little child within us who hurts, who was rejected” (Stapletone 1976, 10). We can then experience healing as “that little child within each of us” is forced to reconcile with the “healing love of Jesus Christ” (Stapleton 1976, 10).

A Word of Caution

While readers will gain insight into how inner healing functions in The Gift of Inner Healing and will read moving stories where it proved effective in Stapleton’s ministry, we must remain cautious about making absolute claims or formulating a unified response to every case. In my own work, particularly in regular engagement with those experiencing homelessness, marginalization, and long-standing unhealed trauma, I have yet to encounter a unified or formulaic approach to healing and restoration. That said, I do believe in the process of inner healing. I have experienced it personally, witnessed it in the lives of others who were open to it, and participated in moments where genuine healing and liberation occurred. I also believe there are times when a deeper level of healing is necessary, including the healing of memories, where we must “deal cleanly and precisely with the root problems,” because, as Stapleton notes, these issues “greatly determine how we respond to each moment in life” (Stapleton 1976, 15).

Often, healing is not just about naming the problem or seeing it, as the social sciences frequently speculate it feels to me. In Jungian fashion, Stapleton believes it is addressing not just seeing or naming. What separates Stapleton from Jungian practices is that it is the healing light of Jesus that brings restoration and reconciliation to their lives. That light primarily comes through prayer, because prayer (seemingly with others present) uniquely “opens the heart so that we can deal with memories buried in emotion” (Stapleton 1976, 27).

The Ongoing Process of Inner Healing

Stapleton is quick to mention that this is not a one-time resolution. She describes her own story as a process and freely shares that “inner healing is a ladder, not a single rung; a process, rarely a one-time event” (Stapleton 1976, 90). Like an onion, there are always layers after layers until we reach what lies at the center. Even when we know what lies at the center, there seems to be a regular taking thought captive action that needs to take place to ensure healing, Stapleton’s own words are that “One of the basic principles of inner healing is that this exercise of “cutting the emotional cord” has to be repeated. Growth requires time, and repeated reinforcement of the new positive pattern forms habit” (Stapleton 1976, 42-43).

An Invitation to Inventory

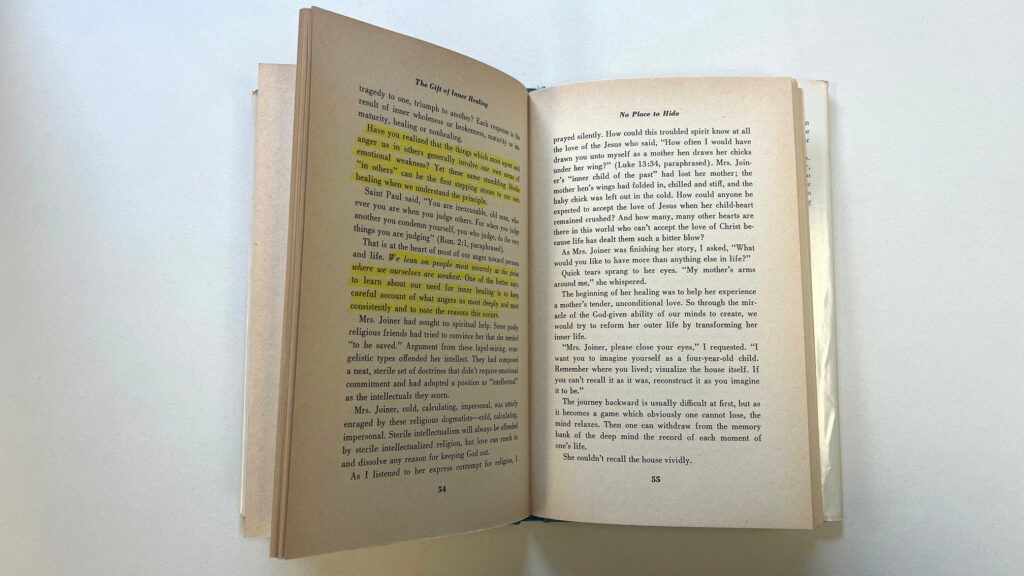

Throughout the book, readers encounter a number of pithy statements that invite honest self-examination. We often attempt to cultivate happiness, joy, and contentment through external factors, yet just as those external comforts fail to cover our pain, negative external circumstances are frequently blamed for our unhappiness or lack of lasting joy. Stapleton suggests that what we display in response to external pressures is often behavior that “expose[s] the negative material within our own subconscious” (Stapleton 1976, 53). Readers are also challenged to recognize that the judgments we hold toward others frequently point to unhealed areas within our own lives. She writes that “the things which most upset and anger us in others generally involve our own areas of emotional weakness” (Stapleton 1976, 54). One of her most memorable observations reinforces this insight: “We lean on people most severely at the point where we ourselves are weakest. One of the better ways to learn about our need for inner healing is to keep careful account of what angers us most deeply and most consistently and to note the reason this occurs” (Stapleton 1976, 54). For me, kairos moments often emerge when I take inventory of the highly emotional, anxious, angering, overly joyful, or unsettling moments of daily life.

A Critical Thought

On the critical side, the book is a very short read, one that will take most readers no more than an hour or two, even with reflection. Additionally, the chapter titled “Is Healing of the Memories Scriptural?” reads less like a biblical treatment and more like an apologetic defense of Stapleton’s credibility in response to a visiting pastor who criticizes her. Despite my belief in inner healing, I agree with many critics that it is difficult to make a strong scriptural case for the concept of “healing of memories.” Jesus, as God in the flesh, was not psychoanalyzing symptoms, yet he consistently guided people toward the roots of their behavior. In cases such as Peter’s denial, Jesus addressed repetition by restoring and reorienting the heart rather than dissecting memories. Other voices have explored this work with greater scriptural and theological depth. Francis MacNutt and Dallas Willard, along with more recent thinkers such as Curt Thompson and Charles Kraft, offer more robust frameworks for understanding healing and formation. For this reason, I wish Stapleton had omitted the chapter altogether. At times, it feels emotionally reactive and defensive, possibly reflecting unhealed areas in her own life, though that is my interpretation.

Highly Recommended

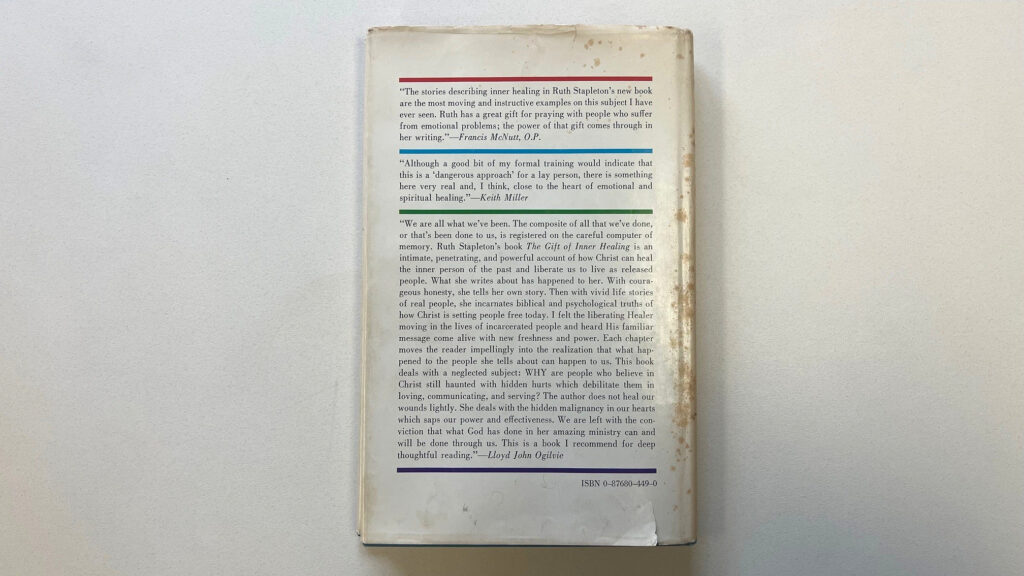

The book does include strong endorsements from Lloyd John Ogilvie and Francis MacNutt, both of whom I respect. MacNutt affirms Stapleton’s ministry from firsthand experience, while Ogilvie perhaps best captures the heart of the book, writing, “She deals with the hidden malignancy in our hearts which saps our power and effectiveness” (Stapleton 1976, back cover). This is indeed the fruit of her work. Stapleton ministered to stay-at-home mothers, working fathers, pastors, and even public figures, including Larry Flynt, who credited her with playing a role in his religious conversion and life changes.

The Final Take on The Gift of Inner Healing

Near the end of the book, Stapleton offers a compelling metaphor, describing the subconscious as childlike, teachable, and profoundly shaped by past experiences (Stapleton 1976, 90). She argues that healing requires reprogramming what has been distorted, replacing it with material aligned with the love revealed in Jesus Christ. As a woman leading boldly in a time when such leadership was rare, Ruth Carter Stapleton remains both compelling and challenging. She lived quietly yet ministered widely, reminding readers that we do not choose whom God sends us to. Her warning against pride and false humility alike is needed. I hope that the church continues this work of healing, grounded not in cultural definitions of wholeness but in a deeper, richer engagement with Scripture than Stapleton herself sometimes provides.